This story originally appeared in the July/August 2024 issue of ESSENCE magazine, on stands June 25.

At the southern reach of the United States map, and about 50 percent below sea level, lies New Orleans. It’s a predominantly Black port city, surrounded by water and known for its music, food and entertainment. New Orleans’s vibrant artistic expression, collective resistance and cultural innovation are rooted in Black people’s survival within what was once the largest slave market in the country. To understand the role of slavery in the creation of America is to recognize the foundational impact New Orleans has had on the country—and the world at large. Today, alongside NOLA’s historical contributions, its Black influence can be heard in the bounce samples that propel songs to global-hit status; tasted in the widespread effort to recreate Creole cuisine; and experienced through the social freedoms made possible by Black people in New Orleans and their determination to thrive.

“Won’t Bow Down”

Authentic change happens from the ground up. Before the French colonial founding of New Orleans in 1718, the Indigenous land was a trading post known as Bulbancha—a Choctaw word meaning “place of many tongues.” Native American tribes cultivated the swampland, coexisting with land, spirit and water. In 1719, the first ship bearing Africans trafficked from the Senegambia region arrived in present-day Algiers Point. Their forced labor built New Orleans as they drained swamps, constructed levees, grew rice, harvested sugarcane, crafted ironwork and laid bricks.

These early arrivals also managed to retain their West African culture. Many of them refused to adapt to oppression in their new land; their defiance is often proclaimed in Black Masking Indian tradition as “Won’t bow down. Don’t know how.” It was in this spirit that Charles Deslondes led more than 500 enslaved people in an 1811 rebellion. They intended to establish the city as a free Black republic. Although they met a brutal fate, their resistance was recorded as one of the largest slave revolts in American history.

Many elements of New Orleans culture stem from the African resistance to Code Noir, the 1724 “Black Codes” of Louisiana. These codes attempted to regulate the lives of Black New Orleans, with the enforcement of Catholicism as the mandatory religion (resulting in a large population of Black Catholics) and Sunday designated as “rest day” for enslaved people. Enslaved Africans and free people of color used Sundays for ceremonial gatherings—holding drumming circles at Congo Square, in the Tremé neighborhood. Marie Laveau, voodoo queen and devout Catholic, lived nearby and was reportedly a Congo Square regular. Most Black New Orleans residents still regard Congo Square as holy land; it’s used for spiritual and musical events.

The Origins of Jazz

The roots of American music are found in drumming circles of Congo Square—the only place in New Orleans where enslaved Africans could gather openly for an extended period. Enslaved people in other parts of the Americas were banned from using drums, but they were allowed to retain the instrument in New Orleans. The drum was at the center of activities in Congo Square. Enslaved and free gathered to practice ancestral chants, call and response, improvisation, and rhythmic patterns that laid the groundwork for jazz. And from jazz came everything: R&B, blues, rock ‘n’ roll, bounce, pop and hip-hop. Jazz was one of America’s first original art forms, and Louis Armstrong was arguably America’s first Black superstar. New Orleans launched modern music, from the drum to the beat. The Great Migration of Black southerners to northern regions took our artists nationwide—and the sound followed, spreading the artistic influences of New Orleans into the mainstream. There was the early work of Mahalia Jackson, Fats Domino and Allen Toussaint, and also the transformative sounds of Trombone Shorty and Wynton Marsalis. Hip-hop brought another cultural shift, when Cash Money Records took over “for the ’99 and the 2000” and Master P showed the music industry “how to slang a record out the back of your trunk.”

Building Community

Often regarded as the oldest Black neighborhood in the country, and located on land once occupied by a plantation, Faubourg Tremé (home of Congo Square) evolved into an ironic reclamation of history, as free people of color acquired over 80 percent of the property. “They were wealthy. They had their own businesses,” says Fatima Shaik, author of Economy Hall: The History of a Free Black Brotherhood, who has family roots in Tremé. “They were active in government right after the Civil War. They were registering people to vote in 1865, five years before we even had a constitutional amendment. So, we had that kind of power; that’s the part that’s not in history. We’re seen as the victims of history, but we were very active members in the creation of history.”

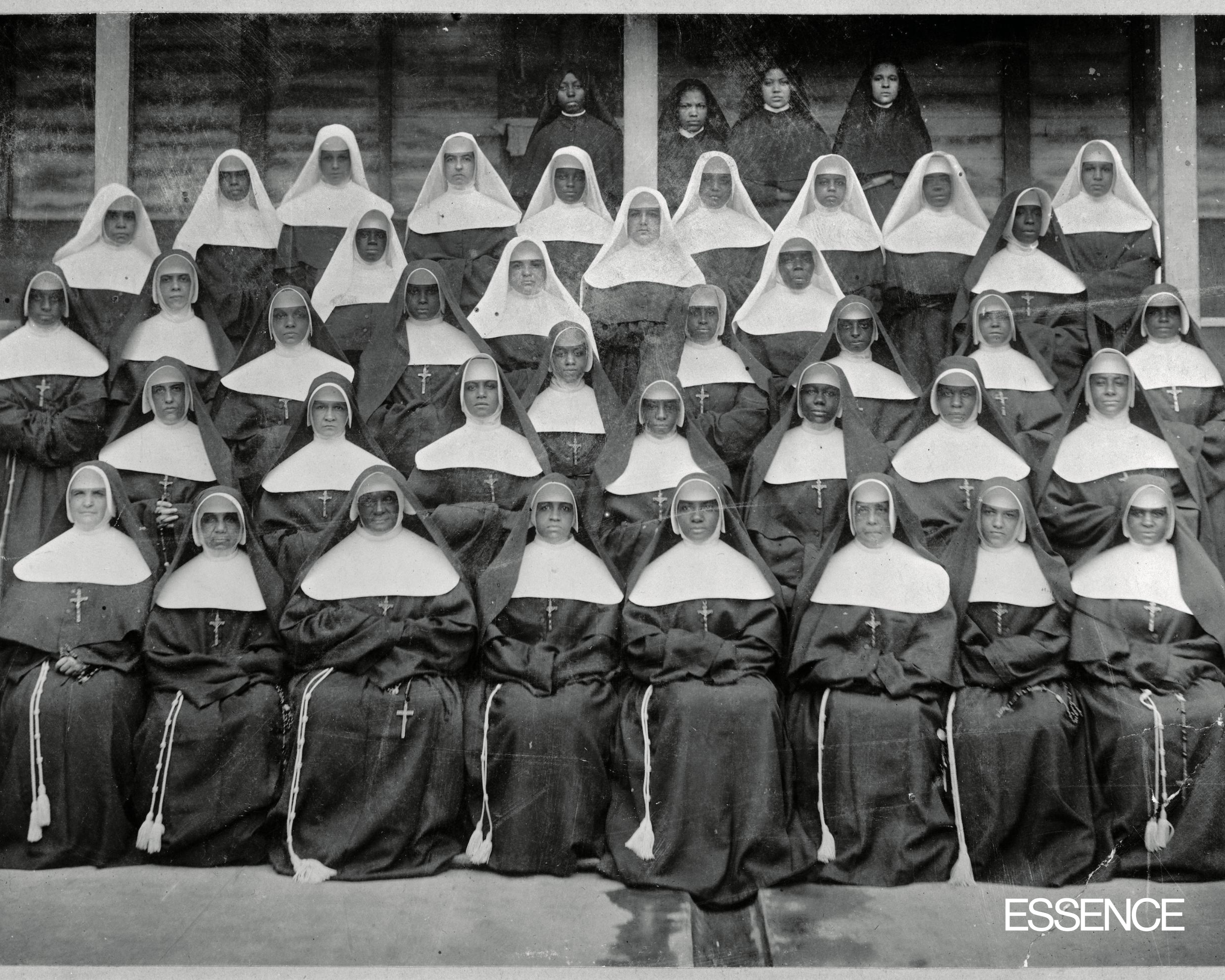

Saint Augustine Church, the oldest Black Catholic parish in the U.S., is a Tremé landmark founded by free people of color. They collectively purchased pews in which enslaved people could worship—an unprecedented act. Some notable parishioners were Homer Plessy (plaintiff in the Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” case), Sidney Bechet (jazz musician) and Venerable Henriette Delille (founder of Sisters of the Holy Family). Delille also cofounded Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with financial support from Thomy Lafon, one of the wealthiest Black people of the 19th century. It was later renamed Sisters of the Holy Family; and Delille is now on the path to canonization as the first Black American saint.

Cooperative Economics

New Orleans’s large population of free people of color created social and political advancements, a hundred years before the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez founded The New Orleans Tribune in 1864; it’s the oldest Black daily newspaper in the country. Economy Hall was a free Black brotherhood in Tremé that revolutionized musical, political and social change. “They tried to get rights for everybody in the community, and that’s what was going on there before it was a musical venue,” says Shaik. “It was a place where people were trying to uplift each other.”

The Economy Society paid dues for member burials when White funeral homes declined, honoring the dead through a jazz funeral. The jazz-funeral procession begins with a slow dirge, as mourners march toward the final resting place, followed by an upbeat tempo, with dancing and “cutting loose” to send off the deceased properly. The casket, brass band and family form the “first line”; the community following them is the “second line.” Today, second lines are a regular Sunday ritual, independent of jazz funerals.

“So often, New Orleans culture is seen as just ‘entertainment’—but there’s a lot of spiritual and healing work that’s taking place in these traditions, specifically the second lines,” says New Orleans native Edward Buckles, Jr., the filmmaker who directed the documentary Katrina Babies. “In my 10 years of documenting this tradition, I’ve witnessed kids and social aid and pleasure-club members feeling like superstars on a Sunday, even if just for those few hours. They’re all there, releasing something. Here, we take the weight of the world we carry and create a sense of freedom in how we gather, mourn and celebrate.”

Second Line Sundays often cross “Under the Bridge” on Claiborne Avenue, where the Tremé neighborhood meets the historic Seventh Ward. It’s where Black New Orleans routinely congregates—now under painted concrete columns where oak trees once stood. This avenue was a “Black Wall Street,” lined with Black-owned businesses, during Jim Crow segregation. But in the 1960s, a highway was constructed that cut through this thriving district, under discriminatory “urban renewal” policies. Despite this, Black New Orleanians gather on Claiborne on Sundays. They celebrate Mardi Gras Day; they witness the handmade suits of the Black Masking Indians, honoring the history of Africans who escaped enslavement and Native Americans who aided them.

“What people don’t understand is that the Black community in New Orleans has been strong for hundreds of years,” says Shaik. That has resulted in solid support of the city’s Black-owned businesses. Across Claiborne is the renowned Dooky Chase Restaurant, where Leah Chase and her Creole cuisine fed a community and a movement, offering a haven for activists like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to meet.

Riding for Freedom

New Orleans also played a crucial role in advancing civil rights in education. “The New Orleans Four” of Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, Gail Etienne and Ruby Bridges bravely led the desegregation of public schools as little girls—and prompted shifts toward desegregation and racial equality in our country’s school systems.

Xavier University of Louisiana, an HBCU, also helped the cause. As the only historically Black Catholic university in the nation, and a leader in STEM, it was a central institution for activism. “I became of counsel for the law firm that represented the Civil Rights Movement in New Orleans,” recalls Norman C. Francis, J.D.,retired Xavier University president of 47 years and the longest-serving university president in the U.S. Xavier’s civil rights activists included students arrested during sit-in protests. Francis supported their civil disobedience: “I said that’s the thing to do.” He recalls Rudy Lombard, Ph.D., the courageous local CORE chairman and a New Orleans native, entering his office with a request for Xavier to shelter the Freedom Riders; they had been brutalized in Alabama and denied hotel rooms. “Rudy said, ‘They’ve gotta have a place to stay,’” Francis recalls. “The first group of cab drivers came in with the Freedom Riders, all bloody and so forth—and we housed them in secrecy on the third floor of the dormitory.”

One of the Freedom Riders, Jerome “Big Duck” Smith, founder of the Tambourine and Fan youth organization, played a prominent role in American history when he met with then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy in 1963 and fearlessly asserted, “What you’re asking us young Black people to do is pick up guns against people in Asia, while you have continued to deny us our rights here.” Following that meeting, Kennedy proposed the Civil Rights Act.

A Personal Witness

My own identity was not formed by the state textbooks or U.S. history classes that have often omitted our narratives and contributions. Rather, it was solidified by my lived experience, growing up as a Black native New Orleanian. Outside the doorstep of my predominately Black, New Orleans East neighborhood, I internalized the Black history around me—and saw myself in the legacy of our ancestors and culture bearers. I now recognize “us” in everything around me; and I know with certainty that the story of America is not complete without the story of New Orleans. As residents of a global tourist destination that has miraculously maintained its mystique and cultural sovereignty, New Orleanians often live in our own world—while influencing the world around us. In 2019, I crafted the phrase “New Orleans Is a Black Woman,” as a metaphor for how my home is so widely imitated, yet so often goes overlooked and uncredited for all that “she” has given our nation. It is time we give this Black woman her just due.